FIRST POSTED: 01/10/20

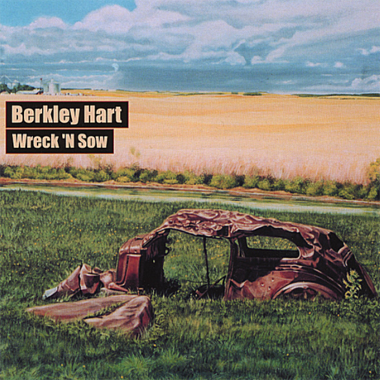

“Barrel of Rain” is a song written by Calman Hart, one half of the duo Berkley Hart, and it appeared on their album “Wreck ‘N Sow”, released in the year 2000. Earlier this year I posted a video of the song on facebook and I described it as a “pretty song”. Immediately after hitting the ‘send’ button, and even more so afterwards, I regretted that. ‘Barrel of Rain’ is without doubt a pretty song but it is so much more than that. I felt – and still feel – bad about damning this fine song with faint praise when it deserves a more considered opinion. What follows is an attempt to make up for my dismissive (ab)use of the adjective ‘pretty’.

I first heard this sung by Martin Giles and as I am totally unqualified to comment on the musical aspects, the following remarks are based on comments from him. Martin states that ‘Barrel of Rain’ is fairly easy to play, having only three chords, if you are familiar with ‘Travis picking’ (see here for info on that) and that even if you are a strummer rather than a picker they are still the same chords and is apparently uncomplicated. He adds that the tempo is quite interesting, in that, being a ballad, you’d expect around 100 beats per minute but in fact it’s 130 bpm – something that he thinks can be explained by the need to ‘push’ the story along as it could, given the dramatic events in the narrative, seem quite sad and dirge-like if the tempo were slower. It seems slower than it really is, I guess. Most importantly for my analysis of the lyrics is that he describes the music as “So much said harmonically with just three chords” and the lyrics as “So much said, with so few words”, something I will elaborate on soon.

The song (YouTube audio version here) tells of a farming couple living in Kansas some time in the late 1920s or early 30s. It describes their life on the plains, hard at the best of times – of which there were few – and the backbreaking and heart-breaking blows that they are subjected to due to the vagaries of the weather and the cruelty of the resulting economic situation.

The first formal aspect of the song that struck me was the symmetry of the song; the first two lines of the first verse are repeated with a slight variation in the last verse, bringing a satisfying sense of closure to the song. The opening two lines are…

“Her pride and his joy was raven black

It ran like a river of silk down her back.”

… while the opening lines of the last verse read…

“Her pride and his joy is now white as milk

And it runs down her back like a river of silk”

We also see that this linear narrative begins with the past tense “was raven black”, and in the final verse it uses the present simple “is now white as milk”, with the word ‘now’ serving to emphasise that the woman is still alive. It is interesting too to see how Hart cleverly uses the expression “Her pride and his joy” which both refer to her hair; she is proud of her long black hair and it gives him joy to see it in its flowing magnificence. Hart’s economy of words is impressive here; it’s not easy to explain this in only five words. The complicity, and love, between the couple is also significantly mentioned so early in the song (lines 3 and 4) where the text says …

“She brushed it every morning one hundred times,

And he washed it for her on Saturday nights”

… re-emphasizing her pride in her raven black hair and his pleasure/joy in washing it for her.

We also see in these two extracts the way that the English language allows the writer to describe something using similes in two different ways: Firstly he describes her hair (and his joy) as ‘raven black’ and in the final verse he uses an expression that more overtly draws a comparison, saying that her hair was “(as) white as milk”. Those of us brought up on the Child Ballads have heard countless songs referring to ‘milk-white’ steeds or ‘cherry-red’ lips and of course we could lay the sentences out in this way, saying that the steed was ‘as white as milk’, or that the fair maiden’s lips were ‘as red as cherries’, but Hart is nimble enough to be both economical in his words in the first verse and flexible enough – in the final verse – to use a different manner of description in order to help his rhyme. This is a useful characteristic of the English language and the romance languages do not have an equivalent; they would have to express the simile in the form “as X as Y” because there is no available alternative, or literal translation, to ‘raven-black’, etc.

The second line is each of the above couplets is also interesting: in verse 1 (line 2, below) Hart writes “it ran like a river of silk / down her back”, while in the closing verse he writes “And it runs down her back / like a river of silk”. Without getting too much into syntactic patterns, we could mention here that the complementation of the verb ‘to run’ allows us to ask the question ‘How does it run?” and also “Where does it run?”; two adverbial expressions which in these two couplets are alternated. Line 2 talks of how it ran before saying where it ran. the closing lines reverse the elements and inform us of where it ran before mentioning how it ran. No big deal, you may think, but it does have the huge advantage of allowing the ‘raven black’ to rhyme with her ‘back’, while the alternative version allows Hart to rhyme ‘silk’ with ‘milk’. Very economical and very cleverly done, I think.

If verse 1 (lines 1 to 4) sets the scene, then verse 2 (5-8) begins the sad narrative of their life in the mid-west.

“Then drought struck the heartland in 1935

They didn’t have water for Saturday nights

It all seemed so hopeless so she cut it with the shears

And he held her close and said through her tears”

So disaster strikes in the form of a drought which simultaneously ruins the crop and prevents the weekly hair washing, leading to such frustration in the woman that she cuts off her hair, not with a pair of household scissors but with the agricultural shears that she probably found in the barn. This causes him to make her a promise: he’ll build her a rain barrel so that she will be able to wash her hair and never have to cut it again. He states, ominously, that “if it’s the last thing I do on this earthly plane I’ll give you a barrel of rain.”

“I’ll build you a barrel to catch the rain

To wash out the dust of the Kansas plain

I swear you’ll never have to cut your hair again

If it’s the last thing I do on this earthly plane

I’ll give you a barrel of rain”

Verses 1 and 2 – like all the other 4-line verses – are in AABB format (black/back ; times/night) (five/night ; shears/tears) etc, but the four choruses are five lines each and are in AAAAA format, and as ‘rain’ is always the last word of each chorus, then the previous four lines all rhyme (sometimes slightly less than perfectly) with that word (‘rain’, ‘plain’, ‘again’, ‘plane’, ‘rain’). In this first chorus – see above – (but not the others) the rhyming words also form a palindromic sequence (read backwards, the five lines still end with ‘rain’, ‘plane’, ‘again’, ‘plane’ ‘rain’). This could just be a coincidence, of course but maybe not; the song is written with such skill and ability that I doubt if Hart was unaware of the palindromic sequence in the first chorus.

So the husband sets about fulfilling his promise to his wife; after his working day is over he works on the barrel, building it out of some staves taken from a chest of drawers, making it watertight with leather and tar and when it is finished to his satisfaction he arrives at the last part of the plan; a prayer to the heavens (literally) for rain to bless his land and allow his wife to wash her hair.

Then he got to his knees and prayed in the yard

“If you give me this, Lord, I’ll never ask for nothing again.

Just a little thundercloud now and then

To give her a barrel of rain”

‘Barrel of Rain’ is a pretty song, but it’s also tragic. Neither his promise to his wife nor his plea to the heavens brings any relief. The rains never come and he feels destroyed because he is unable to provide water for his wife’s hair and of course for the crops, their livelihood. Worse of all, the wife could see every morning that the cloudless sky foretold a dry day and therefore misery for the husband who felt that he’d made a promise to his wife that he was unable to fulfil, and simultaneously he had entered a ‘deal’ with God to provide the rain and never ask for anything else. He is both betraying his promise to his wife and being betrayed by God and this double betrayal was eating him up inside. The crops fail and the bank foreclose on his property, leaving him with no solution but to accept his fate, and this breaks his spirit, and he dies, broken hearted.

But the rain never came, the barrel sat dry

She watched as the truth of it ate him alive

Then God took the crops, and the bank took back the land

When his spirit broke, he just folded his hands

The wife reflects angrily on the cruel nature of the situation: she looks down at the parched grave of her husband and thinks of all the hard work that he put into the farm, and all for nothing. She screams in anger and frustration that her husband didn’t deserve this fate.

“He didn’t want much and he never complained

Dear God, he just wanted a barrel of rain.”

The next verse follows immediately after the chorus but the text makes it clear that many years have passed, and many miles travelled, since the husband’s burial. She is old, or at least much older, as her hair is now long (again) and as ‘white as milk’. She no longer lives in the dust-ridden plains of Kansas, but on the Oregon coastline, a much wetter place and one much more likely to provide her with enough water to deal with her weekly hairwashing. There is certainly a geographical difference between where she lives now and where she lived before, and similarly we feel that she has travelled a great distance in time too. However, there is one, and only one, thing that connects her to her past life as a farmer’s wife in Kansas; the barrel made for her by her husband.

All that she brought to these Oregon shores

Was a barrel made out of an old chest of drawers.

In the song’s final chorus, we hear about the neighbours’ image of her as ‘that crazy woman who looks at the sky all the time’; a ‘crazy woman’ who, at the weekend, if the weather is fine, leaves her house, where presumably she has a working bathroom and shower, and thinks back to the days when she was a young married woman, and goes out in full view of her neighbours and washes her hair as she used to do before she was widowed; outdoors, using rain from a barrel her loving husband made for her many years ago, in another time and another place.

The neighbors all whisper that she’s insane

The way that she stares at the driving rain

And waits for the gutters to fill it up again

Then on Saturday nights if the sky is tame

She washes her hair in a barrel of rain.

There are numerous versions of a quote that I think is relevant here and I cannot definitively say who really said this first or said it best, but Mark Twain (reportedly) said “I didn’t have time to write a short letter, so I wrote a long one instead.” Henry David Thoreau’s version (reportedly) is “Not that the story need be long, but it will take a long while to make it short.” Whatever; the point here is that the music here is very economical (only three chords) and the lyrics, as we have seen, are able to express complex thoughts and situations in very few words and neither the music nor the lyrics give the/this listener the impression that something is lacking, or that the song would have benefitted from more musical complexity and/or more lyrics. Just as the husband was able to craft something lasting, useful and perfect when making the barrel, Calman Hart shows himself to be a master of musical and lyric economy and demonstrates here that songs can be crafted with as much skill as carpentry.

Her pride and his joy was raven black

It ran like a river of silk down her back

She brushed it every morning one hundred times

And he washed it for her on Saturday nights

Then drought struck the heartland in 1935

They didn’t have water for Saturday nights

It all seemed so hopeless so she cut it with the shears

And he held her close and said through her tears

“I’ll build you a barrel to catch the rain

To wash out the dust of the Kansas plain

I swear you’ll never have to cut your hair again

If it’s the last thing I do on this earthly plane

I’ll give you a barrel of rain”

So he worked in the evenings when he finished up the chores

He cut out some staves from a chest of drawers

He bound them with leather, sealed them with tar

Then he got to his knees and prayed in the yard

“I’ve built this barrel to catch the rain

To wash out the dust of the Kansas plain

If you give me this, Lord, I’ll never ask for nothing again

Just a little thundercloud now and then

To give her a barrel of rain”

But the rain never came, the barrel sat dry

She watched as the truth of it ate him alive

Then God took the crops, and the bank took back the land

When his spirit broke, he just folded his hands

As the sun beat down on his thirsty grave

She thought of the fields that he plowed in vain

She screamed at the sky with all her rage and pain

He didn’t want much and he never complained

Dear God, he just wanted a barrel of rain

Her pride and his joy is now white as milk

And it runs down her back like a river of silk

All that she brought to these Oregon shores

Was a barrel made out of an old chest of drawers

The neighbors all whisper that she’s insane

The way that she stares at the driving rain

And waits for the gutters to fill it up again

Then on Saturday nights if the sky is tame

She washes her hair in a barrel of rain.

Great analysis of a great song! Thanks Mike (and thanks Martin for bringing it to us). Like all the best analyses, this sends you back to the song with increased appreciation. Love it.

I agree with Jeff. Great analysis of this great song. Hope to here more.